Ocean Crusaders have written a lot of about plastics on our website, and we have more than once highlighted the concept of the ocean gyres, where so-called “islands of trash” float, trapping fish, choking birds, and grow larger with the passage of time. Despite widespread concurrence on the subject, confusion remains, due to the fact that these gyres are not actually floating mats of garbage the size of entire states, an image fostered by some of the earlier, more publicized reports. They are, rather, concentrations of surface and sub-surface floating debris at the convergence of ocean currents. But how much plastic is really there? Conflicting reports and opinions have made it difficult to get a secure handle on the magnitude of the problem.

However, Sea Education Association (SEA) recently published an article in Science reporting on 22 years of data collected in the North Atlantic by their faculty and students on this very issue, giving concrete evidence of the “floating trash heaps”.

Every year SEA sails the Atlantic, Pacific and Caribbean with upwards of 25 college students and 10 professional crew aboard the Corwith Cramer and the Robert C. Seamans. SEA Semester students combine an interdisciplinary academic program of oceanography, history, literature, marine policy and nautical science with a six week open ocean voyage. For forty years and one million miles sailed, SEA has been the only program in the world to teach college students about the ocean in this way. From 1986 to 2008, in the Atlantic Ocean, over 4,887 individuals have participated in this study of ocean-bound plastics, collecting and cataloguing over 64,000 individuals pieces of plastic, most only millimeters in size. Through these efforts, SEA has amassed an “unrivaled dataset” that helps describe the extent of this pollution, and can teach us about the fate of plastics in the ocean.

So what did SEA find?

Over those 22 years, SEA conducted 6,136 surface plankton net tows on annually repeated cruise tracks throughout the North Atlantic and Caribbean Sea. Sixty-two percent of all plankton tows contained some amount of plastic, with the highest in a single 30-minute tow being 1069 individual pieces. To scale, that equals 580,000 pieces per square kilometer (about 360,000 per square mile). That sounds like a LOT of plastic, but many of these pieces are less than a millimeter thick. While it makes for a less thrilling visual, it does make for a more dire outlook for the ocean and its fauna. The data reported by SEA in Science only accounts for floating surface debris. It does not account for plastic that has sunk below the surface or to the sea floor, or been ingested by fish, mammals or birds. Over 22 years, that could be quite a lot of plastic.

To get a sense of how much plastic could be in the ocean far below the surface, where SEA’s plankton nets could not get to them, try this exercise:

Find a plastic bottle (Franklin Spring Water, Gatorade, etc.). Remove the cap, fill the bottle to the brim with water, and submerge in a tub or a bucket (make sure to get all the bubbles out). Does it sink or float? Now submerge the cap. Sink or float? If you were using a Franklin Spring bottle, or another brand with a 1 recycling number stamped on the bottom, it should have sunk (this is one of the most dense plastics). The cap (probably made of less dense HDPE #2) should have floated. Now think about this: Every year in excess of 300 BILLION plastic bottles are used around the world. We don’t know exactly how many of them reach the ocean, but if you’ve ever seen a bottle lying on the ground and didn’t pick it up, chances are, it’s in the ocean now. 80% of all marine debris is thought to originate on land.

But back to the Atlantic.

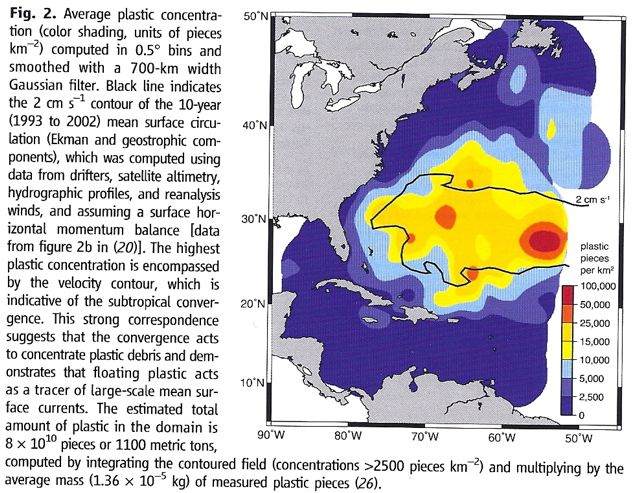

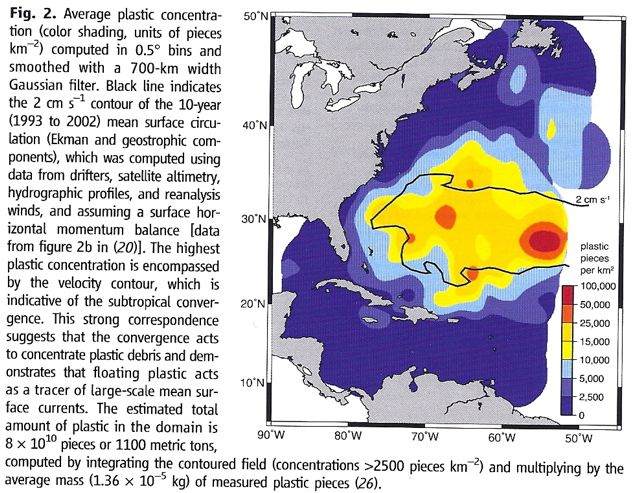

Compiling the data, SEA discovered that plastic does indeed accumulate in the North Atlantic Gyre (see image labeled Fig. 2). Not surprisingly, the highest densities of plastic they collected are concentrated between 22 and 38 degrees latitude in an area also known as the Sargasso Sea (or the Bermuda Triangle).

Though this data set displays no significant increase in plastic accumulation between 1986 and 2008, it does show persistent high concentrations of plastic. During this time period globally, there is a very significant increase in the production and discarding of plastic; however data does not account, as we mentioned previously, for sinking, ingested plastics or plastic fragments smaller than 1/3 mm, the mesh size of the plankton net. Readers should also remember that these gyres are not firmly constrained sites, and that currents carry water and debris constantly throughout the interconnected ocean.

Though this data set displays no significant increase in plastic accumulation between 1986 and 2008, it does show persistent high concentrations of plastic. During this time period globally, there is a very significant increase in the production and discarding of plastic; however data does not account, as we mentioned previously, for sinking, ingested plastics or plastic fragments smaller than 1/3 mm, the mesh size of the plankton net. Readers should also remember that these gyres are not firmly constrained sites, and that currents carry water and debris constantly throughout the interconnected ocean.

The ultimate message here is that plastic, once created, doesn’t go away and a lot of it ends up in the ocean, swirling around for eternity, confusing fish and tainting our food supply.

So what can you do?

- Reduce – Use less plastic! Give up straws, single-use bottles and disposable forks.

- Reuse – Used some plastic? Save it, use it again!

- Recycle – If your plastic is used up, make sure to recycle it properly. Find out if your town has single-stream or separated recycling and only recycle those items your local plant can handle.

- Read more – Read the full SEA article in Science

- Check out the more recent data collected in the Atlantic

- Learn more about SEA and how you can support their work www.sea.edu

- Enroll in a semester at sea and help SEA continue their data collection, see how they do collect data in the video below:

Courtesy of Sailors for the Sea – www.sailorsforthesea.org